I had heard about the fire when I was growing up. Each winter the oldtimers would remind folks of the Fire of 1904. As a kid I really didn't listen, how sorry I am now. Later as I became more interested in St. Pat's story, I found that the Sisters of Notre Dame kept a Journal of daily events in the convent. I was fortunate to be able to sit with the original Journal and read the Sister's handwritten account. During the entire fire the nuns knelt outside the firedoor between the church and the convent with the arms outstretched praying for intercession. The account later described the tears of the priest and people viewing the damge.

The rectory got a phone call a few years ago of someone asking to meet me. A certain individual had some items of historical significance that he wanted me to see. The family had been long time parishioners. The individual's family was actually present at the time of the fire and picked up some souvenirs from the church. He thought it was time for them to come home. Today they are part of the Parish Archives. One is a piece of marble that was the base of a statue. I'm pretty sure by matching the stone it was the base of a statue of Saint Bridget or Columba. These 2 statutes once stood on each side of the altar. (During this coming year's Irish Cultural Week the images of the 2 saints will be restored to the church.)

You might think that such an occasion is random, but not so. Many of the items in the Archives have made their way back in such a way. I've also gotten phone calls from folks who invite me to see their treasures and then be told they cant part with them. I recently heard of some items being thrown in the trash since the children had no idea of their importance to our history. If you find yourself in a similar situation, give St Pat's Rectory a call- 978-459-0561.

The Grand Fires of 1904 – St. Patrick’s Catholic Church; Lowell, Massachusetts

Note to readers: The St. Patrick’s Church fire of 1904 occurred just one day before the Fellows Block fire covered in last week’s post. This post marks the third installment of the Grand Fires of 1904 series.

On Monday, January 11, 1904, Sister Josephine, a teacher at Notre Dame Academy in Lowell, Massachusetts, awoke, rose from bed, and looked out her window at the pre-dawn stillness; it was just minutes after five o’clock in the morning. Only she saw smoke – and lots of it – billowing from St. Patrick’s Church. Sister Josephine rushed from her room and roused two other sisters. Together, the three Notre Dame teachers found the key for the fire alarm box on Fenwick Street, just outside the church’s main gate. Key in hand, the nuns rushed to the parochial residence, rapped at the door, and pulled the bell. Rev. John J. McHugh, in the midst of a week of sick calls, bolted awake, threw on his clothes, and answered the knocking at the door, ready for his next sick call.

Father McHugh saw the nuns – and the smoke in the churchyard behind them. He held the church quite dear. As a boy, he had been a student in its Sunday school and, later, an altar boy to its first priests. Father McHugh called the Central Fire Station on the telephone, and took the key to the fire box to pull the alarm. He struggled with the box; its door wouldn’t open. It was either frozen or broken. He looked back at the growing billows of smoke issuing from the church and gave up on the fire box. He quickly ran inside the basement of the church and set to saving the host and as many sacred vessels as he could carry out.

A crowd began to gather outside the church as more and more of the neighbors, most parishioners themselves, saw the smoke. Mary Ann Saunders, the elderly sacristan of the church and another lifelong member, pushed through the bystanders and rushed toward the burning church. She made her way to the vestry windows on the Cross Street side, broke the glass, and climbed through. She found the vestments, and prepared as big a pile on the floor as her frail but determined frame would allow her to carry. The firemen arrived later to find her at her task, building a small mountain, and ordered her out of the building. She turned, looked at the men, and refused – still determined to save as many vestments as she could. The firemen were preparing to carry all 80 pounds of her out when another priest, Fr. Walsh, happened upon the scene. Both were doubtful that the firemen would save the sacred vestments that Mrs. Saunders had gathered on the floor of the vestry. Fr. Walsh mediated a compromise and the firemen escorted him and Mrs. Saunders from the building and helped them with the vestments. Apparently, Mrs. Saunders was quite convincing.

Other parishioners rushed through the chaos to save sacred and valuable items within the burning church. John Nugent, a member of the Holy Name Society, felt through the smoke and saved two large candlesticks that stood near the main altar. John J. Sullivan carried out several statues, vestments, and other articles. Professor Fred G. Bond, the director of the church choir, ran into the church at great peril to save the church’s collection of music from the choir gallery. The music, which had been brought from Ireland by the late Father Michael O’Brien, was priceless to the church. With the help of the firemen, Professor Bond took several bundles of music and covered others with protective blankets.

Soon, a dozen lines of hose were directed at the church. Chief Hosmer ordered the ringing of a general alarm. The firemen aimed their streams of water at the steeple, the flames continued to lick at its stone and wood. The firemen soon realized that their water would reach only 100 feet up, but the steeple was already fully ablaze – every inch of its 225-foot height. The steeple was doomed.

In its aftermath, Chief Hosmer suffered through significant, and undue, criticism, for initially underestimating the fire, and soon after, for mistakenly concluding that the fire was out. The fire department also received criticism for the antiquated key-operated fire box at the corner of Fenwick Street, which had not yet been replaced by a new handle-operated box. The failure of the key-operated box had been one factor leading to a delay in the reporting of the fire. The fire department also received criticism for not using its water tower to fight the fire and for the underperforming hydrants that provided 100-foot streams of water when streams reaching 225 feet were needed.

Chief Hosmer defended himself in the press as early as the following day, stating that many of the accounts circulating were false. When the fire was extinguished in the basement, he, and several of the priests, had thought the fire was under control when he sent the two companies of firemen home. As soon as he entered the church again, he found that the fire still raged in the three inches separating the wall and the plastering and that this had allowed the fire to work its way up from the basement into the church. Hosmer immediately called the dismissed companies back; they hadn’t gone far and were able to return quickly. Hosmer knew the gravity of the situation when he realized that the fire had progressed into the church’s main floor and he had rung the general alarm. Regarding the water tower, Homer stated that it could not have been used in the situation. Chief Edward F. Hosmer survived the hasty post-fire criticism and went on to serve the Lowell Fire Department for another nine years before he retired, with honor, on May 1, 1913 after 55 years of firefighting, 30 of which were spent leading Lowell’s fire department.

On Monday, January 11, 1904, Sister Josephine, a teacher at Notre Dame Academy in Lowell, Massachusetts, awoke, rose from bed, and looked out her window at the pre-dawn stillness; it was just minutes after five o’clock in the morning. Only she saw smoke – and lots of it – billowing from St. Patrick’s Church. Sister Josephine rushed from her room and roused two other sisters. Together, the three Notre Dame teachers found the key for the fire alarm box on Fenwick Street, just outside the church’s main gate. Key in hand, the nuns rushed to the parochial residence, rapped at the door, and pulled the bell. Rev. John J. McHugh, in the midst of a week of sick calls, bolted awake, threw on his clothes, and answered the knocking at the door, ready for his next sick call.

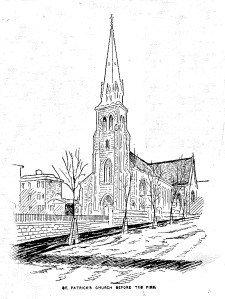

St. Patrick's Church - Lowell, Massachusetts, Before the Fire

A crowd began to gather outside the church as more and more of the neighbors, most parishioners themselves, saw the smoke. Mary Ann Saunders, the elderly sacristan of the church and another lifelong member, pushed through the bystanders and rushed toward the burning church. She made her way to the vestry windows on the Cross Street side, broke the glass, and climbed through. She found the vestments, and prepared as big a pile on the floor as her frail but determined frame would allow her to carry. The firemen arrived later to find her at her task, building a small mountain, and ordered her out of the building. She turned, looked at the men, and refused – still determined to save as many vestments as she could. The firemen were preparing to carry all 80 pounds of her out when another priest, Fr. Walsh, happened upon the scene. Both were doubtful that the firemen would save the sacred vestments that Mrs. Saunders had gathered on the floor of the vestry. Fr. Walsh mediated a compromise and the firemen escorted him and Mrs. Saunders from the building and helped them with the vestments. Apparently, Mrs. Saunders was quite convincing.

Other parishioners rushed through the chaos to save sacred and valuable items within the burning church. John Nugent, a member of the Holy Name Society, felt through the smoke and saved two large candlesticks that stood near the main altar. John J. Sullivan carried out several statues, vestments, and other articles. Professor Fred G. Bond, the director of the church choir, ran into the church at great peril to save the church’s collection of music from the choir gallery. The music, which had been brought from Ireland by the late Father Michael O’Brien, was priceless to the church. With the help of the firemen, Professor Bond took several bundles of music and covered others with protective blankets.

Sister Superior Theresa, of Notre Dame Academy, stood among the bystanders watching the fire, and calmly took hold of the situation. She ordered all gas shut off in the church and all fire doors between the church and academy closed. She thought of her grade school students at the boarding school. Sister Superior advised her nuns not to tell the students of the fire until they were safely dressed and downstairs. Her actions probably saved the school and lives.

The firemen, who had responded quickly, did not find much of a blaze initially, only lots of billowing, blinding smoke. The firemen surmised that the blaze had started in the church’s boiler room in the basement. To gain entry, they broke through the church’s basement door and drove into the smoke escaping the church. The fresh air fanned the flames, but the firemen’s efforts subdued the fire within a short time. Lots of smoke and water still filled the church’s basement, but the flames appeared to be out. Chief Hosmer dispersed some of the firemen and left a few to help in the clean-up. The crowd breathed a sigh of relief. Their church was saved.

But smoke still billowed from the upper part of the church. And it seemed to be growing in intensity. Doubts began to rise through the crowd that the fire was truly extinguished. Perhaps the smoke was still emanating from a fire. Within fifteen minutes, the crowd, the remaining firemen, and Chief Hosmer looked on in horror as flames shot through the church’s roof. The fire still lived inside the church’s walls. Chief Hosmer frantically called back the dismissed firemen. By now, Suffolk, Cross, Fenwick and Adams Streets were clogged with bystanders watching the fire. The police struggled to keep them back, a safe distance from the flames.

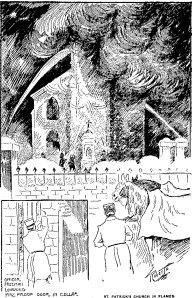

St. Patrick's Church was soon ablaze. Inset: Officer Freeman lowers the fire doors.

Before 8 o’clock that morning, the huge, heavy cross, which had hung on the steeple for the building’s first 50 years, crashed into the interior of the church. The flames could be seen throughout the city – thousands watched as the steeple burned in what some described as “an awful beauty”. When the steeple failed, its spectacular crash sent timbers spilling into the church yard and into Cross Street. Several fell atop members of Hose 11, throwing them to the ground. They survived, though bruised and cut.

The firemen battled the raging fire, sending streams of water toward the church from all four sides. Assistant Fire Chief Norton broke through the main door of the church, but was driven back by the smoke, and almost suffocated. The firemen behind him directed several lines of hose into the church’s interior, but the altar, pews, and the entire front of the church was already lost to the flames.

Several firemen had close calls in the fire. One, whose name was never recorded, was struck when a large piece of plaster, weighing several pounds, struck his helmet and knocked him flat. The fireman remarked “Gee, that was a close call!” as he picked himself up, cognizant of the fact that his helmet likely saved his life. Another, a call man named John Conway, fell through a burning floor and was badly shaken, but not injured.

The fire was extinguished, eventually – but not until midday. Two firemen worked on its last sparks in the bell tower for an hour while the crowd watched from below. By the time the fire was out, St. Patrick’s Church, the city’s oldest Catholic church with origins dating to the 1820′s, lay in ruins – its steeple destroyed, its interior gutted. Its four walls stood, but it was clear that mass would need to be held somewhere else for some time. The church’s marble altar, and every single stained glass window had been destroyed. Parishioners, eager to hold onto any possible memento of their ruined church, sifted through the ruins in the hours and days after the fire to find their metal pew number markers within the ashes.

City official James Conlon offered Fr. O’Brien the free use of Huntington Hall. Indeed, the church would not fully recover from the damage caused by the fire until two years later, in 1906.

The Interior of St. Patrick's Church in Lowell, Massachusetts after the fire

A man scours the ruins of St. Patrick's Church in Lowell, Massachusetts for mementos of his lost church.

In the aftermath of the 1904 fire that destroyed St. Patrick's Church in Lowell, Chief Edward S. Hosmer received much criticism in the local press.

Chief Hosmer defended himself in the press as early as the following day, stating that many of the accounts circulating were false. When the fire was extinguished in the basement, he, and several of the priests, had thought the fire was under control when he sent the two companies of firemen home. As soon as he entered the church again, he found that the fire still raged in the three inches separating the wall and the plastering and that this had allowed the fire to work its way up from the basement into the church. Hosmer immediately called the dismissed companies back; they hadn’t gone far and were able to return quickly. Hosmer knew the gravity of the situation when he realized that the fire had progressed into the church’s main floor and he had rung the general alarm. Regarding the water tower, Homer stated that it could not have been used in the situation. Chief Edward F. Hosmer survived the hasty post-fire criticism and went on to serve the Lowell Fire Department for another nine years before he retired, with honor, on May 1, 1913 after 55 years of firefighting, 30 of which were spent leading Lowell’s fire department.

No comments:

Post a Comment